Who Was Seneca?

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger was born in what is now Córdoba, Spain, around 4 BC, into a wealthy equestrian family, one rank below the senators, the highest social order in the Roman Empire. Over the course of his life, Seneca rose through the ranks of power to stand shoulder to shoulder with emperors. His life was filled with intrigue, politics, and tragedy, yet today he is remembered not for his wealth or influence but for his words, philosophical essays, and letters that continue to inspire.

But who was he really? A Stoic philosopher devoted to virtue, or a career-driven statesman navigating power?

Family and Early Life

Seneca came from an educated and prominent family. His father, Marcus Annaeus Seneca the Elder, was a well-known rhetorician of Italian descent. His mother, Helvia, is remembered through Seneca’s moving Consolation to Helvia, written during his exile in Corsica.

He had two brothers: Annaeus Novatus, later known as Junius Gallio, the proconsul of Achaia mentioned in the New Testament for releasing the Apostle Paul, and Annaeus Mela, whose son, the poet Lucan, became famous for his epic Pharsalia on the Roman civil war.

The Start of Public Life

Seneca went to Rome at an early age to study rhetoric and philosophy, but struggled with chronic illness, possibly asthma. Seeking relief, he spent time in Egypt for its better climate before returning to Rome in 31 AD to begin his public career.

His rise coincided with the reign of Gaius Caligula, the infamous emperor known for cruelty and vanity. According to the historian Cassius Dio, Caligula grew jealous of Seneca’s eloquence and ordered him to take his own life, a sentence withdrawn only when someone reminded the emperor that Seneca’s poor health might soon do the job for him.

Claudius and Exile

Caligula’s successor, Claudius, soon became suspicious of Seneca as well. Accused of adultery with Claudius’s niece, Julia Livilla, Seneca was exiled to Corsica, where he spent eight years in isolation and loss. During this period, he also mourned the death of his only son with his wife, Pompeia Paulina.

Despite the hardship, Seneca continued to write prolifically, refining his Stoic thought and producing some of his most introspective works.

His return to Rome came through the influence of Agrippina the Younger, sister of Caligula and now the wife of Claudius. Ambitious and politically astute, Agrippina sought to secure the future throne for her son, Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, who would later be adopted by Claudius and renamed Nero.

Seneca the Tutor

Agrippina chose Seneca to educate her son, hoping his wisdom and rhetoric would prepare Nero for leadership. When Nero became emperor at just sixteen, Seneca, together with Sextus Afranius Burrus, the head of the Praetorian Guard, became one of the young ruler’s two key advisors.

During the first five years, the Empire flourished under their joint guidance, a period later called the quinquennium Neronis, or “the five good years of Nero.”

But the harmony would not last. When Nero had his stepbrother, Britannicus poisoned and later murdered his own mother, Agrippina, Seneca’s influence began to wane. After Burrus’s death in 62 AD, Seneca requested retirement, even offering to surrender his vast wealth, but Nero refused. To withdraw quietly would make Seneca appear noble and Nero weak.

Still, Seneca retreated from public life, devoting his final years to philosophy and writing.

Who Was the Real Seneca?

Seneca’s writings form one of the richest sources of Stoic philosophy that survives. His Letters to Lucilius, essays, and tragedies reveal both a gifted stylist and a sharp moral thinker. His language is vivid, his wit precise, and his insights enduring.

But Seneca’s legacy remains debated. Was he the philosopher who sought virtue amid corruption, or a political opportunist cloaked in moral language?

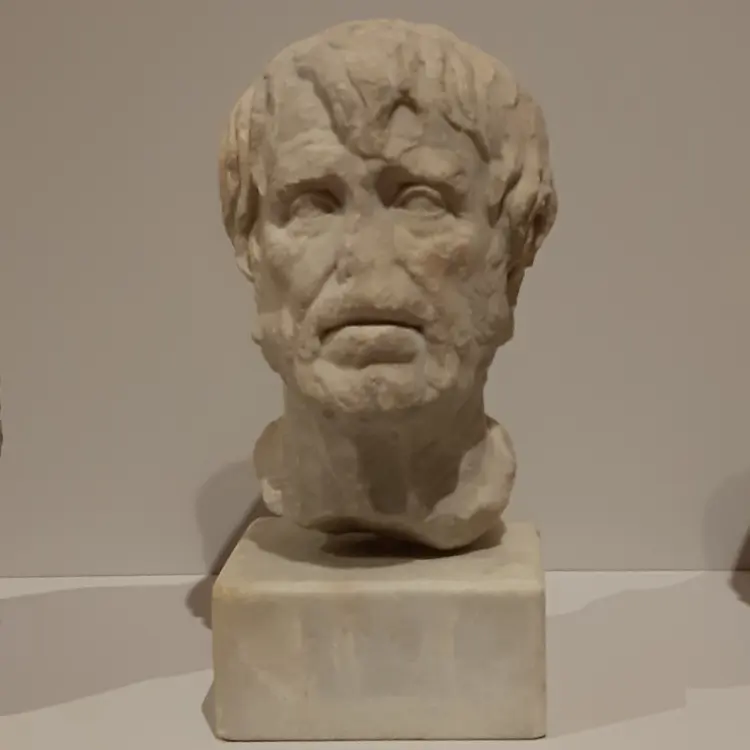

Biographer James Romm explores this paradox in Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero. Two sculptures believed to depict Seneca embody this same tension: one, lean and austere; the other, round-faced and regal, both bearing his name, both mirroring a divided legacy.

Whatever the truth, his words outlived the empire that produced him. His essays and letters remain a treasury of practical wisdom.

Seneca’s Writings

Between 62 and 65 AD, Seneca composed his famous Letters to Lucilius, addressed to a young friend from Pompeii. Though no replies survive, the letters read like a moral dialogue, Seneca shaping the life of a student while reflecting on his own.

He also wrote essays such as On Anger, On the Happy Life, On the Tranquil Mind, On Mercy, and several Consolations. His tragedies, inspired by Greek models, explore themes of fate and moral collapse, while Natural Questions investigates the workings of the physical world, showing that Stoicism embraced both ethics and science.

His works influenced early Christian thinkers, Renaissance humanists, and modern philosophers alike. They continue to resonate because they deal with what does not change: human emotion, ambition, and the search for peace.

Seneca’s Death

In 65 AD, Seneca was accused of involvement in the Pisonian Conspiracy, a plot to assassinate Nero. Ordered to take his own life, Seneca prepared for death calmly, in true Stoic fashion.

Like his hero Socrates, he had long kept hemlock ready for such a moment. Yet his end was far from peaceful. When cutting his veins failed, he entered a hot bath, and finally drank the poison, his strength fading slowly as steam filled the room. His wife, Pompeia Paulina, attempted to follow him in solidarity but was stopped and survived.

Seneca died as he had lived, within the contradictions of Stoicism and power, but steadfast to his principles until the end.

The Relevance of Seneca Today

Whatever we make of Seneca’s personal contradictions, his words continue to guide us. His reflections on anger, grief, time, and virtue speak directly to modern life, to our distractions, our ambitions, and our struggles to live well.

His Letters to Lucilius remind us that philosophy is not an escape from the world, but a way of being within it — deliberate, wise, and humane.

“It is not that we have a brief length of time to live, but that we squander a great deal of that time.”

Seneca, Dialogues and Essays, On the Shortness of Life,1

FAQ: Seneca and His Philosophy

Who was Seneca?

A Roman Stoic philosopher, playwright, and advisor to Emperor Nero (4 BC – 65 AD).

What did Seneca teach?

That philosophy is a way of life, guiding how we think, act, and respond to fortune, not an abstract pursuit.

Was Seneca consistent with Stoic virtue?

Debatable. He lived amid power and wealth, but his writings show constant self-examination and awareness of moral struggle.

What are Seneca’s most famous works?

Letters to Lucilius, On Anger, On the Tranquil Mind, On the Shortness of Life, and On the Happy Life.

How did Seneca die?

By suicide under Nero’s order in 65 AD, after being accused of conspiracy, facing death with Stoic composure.

Want to Explore More Stoic Practices?

Book a free consultation with one of our Stoic Coaches to get support. Or be inspired by more than 100 Seneca Quotes. Listen to the Via Stoica Podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or YouTube.

Author Bio

Benny Voncken is the co-founder of Via Stoica, where he helps people apply Stoic philosophy to modern life. He is a Stoic coach, writer, and podcast host of The Via Stoica Podcast. With almost a decade of teaching experience and daily Stoic practice, Benny creates resources, workshops, and reflections that make ancient wisdom practical today.

0 Comments